In 1965, Herbert Simon predicted that “within twenty years, machines would be capable of doing any work a man can do.” Five years later, Marvin Minsky forecasted that “in from three to eight years we would have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.”

Bringing up these predictions is not necessarily meant to emphasize that roughly 50 years later they’re still a long way from turning real – in spite of the obvious breakthroughs. It’s more about acknowledging the fact that the early founders of AI were overly optimistic about the future of AI. This optimism fueled not only the hype, but also their own dismissal of any criticism – particularly coming from philosophers.

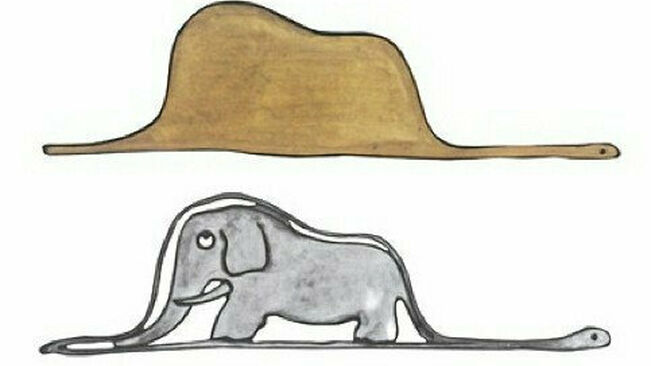

This article is about how philosopher Hubert Dreyfus advanced a powerful critique of the disembodied AI, ushering in the new paradigm of embodied and enactive AI.

How we understand the world

Most exaggerated claims around AI were based on the classical paradigm, which over the years wore many hats – from computationalism and computational theory of mind (CTM) to information processing and GOFAI (Good Old-Fashioned Artificial Intelligence).

For instance, the supporters of the cognition as computation approach assumed that the brain is a computer. Hence, it’s algorithmic. They were very keen on the abstract algorithm – i.e. the program; the hardware embedding the program did not matter all that much. In this case, the implication is that intelligence can grow in artificial systems running on computers in the same way it grows in biological systems running on biological brains.

The paradigm of cognition as computation relies on the Cartesian principle, which basically states that human understanding is all about forming and manipulating symbolic representations. This paradigm builds on top of the Cartesian dualism or the mind-body dualism, according to which humans are made of two ultimate, irreducible components:

- the thinking substance (res cogitans)

- the physical substance (res extensa)

Hence, we are dealing with two types of reality – one resulting from immaterial thinking (res cogitans), the other from thinking with extension in space (res extensa). Res extensa is our body- it takes space. Yet, without res cogitans, our body would be only a mere mechanism, a dead body.

Transhumanists picked up this theory, claiming that the body means nothing and everything is in the mind – or about the mind. That’s why Cartesian dualism is often called Disembodied Intelligence, which means that intelligence doesn’t need a body.

This is an implicit assumption in the idea of achieving Singularity and mind uploading. In his book – “Mind Children”, transhumanist Hans Moravec claims that the mind is just a pattern of information sheltered in the brain. In other words, it’s res cogitans, so it’s immaterial.

He also claims that there’s nothing special about the brain for it to shelter that particular pattern. Therefore, the brain can be replaced, and the mind can be implemented in silicon. This idea leads to another implicit assumption – i.e. the mind can be extracted out of humans. It’s as if one could extract the res cogitans from the human personality.

Hubert Drefyus’s critique of disembodied AI

Hubert Dreyfus, an American philosopher and professor at Berkeley, relied on the works of Heidegger and Merleau Ponty to criticize the Cartesian point of view of disembodied intelligence. According to Dreyfus, human thinking and cognition are not disembodied processes. They are directly tied to sensory motors and bodily functions. Hence, without the body, there’s no intelligence.

Dreyfus explained that human intelligence is not disembodied or pure algorithmic, because it has to deal with the real world. So, artificial agents cannot deal with the real world unless they are embodied. Without a body, it would be all the more difficult for them because reality is infinite. We can only perceive some parts of it, depending on our motivations and our capacities. What’s more, we are designed to perceive only what is essential for our survival.

We do not achieve intelligent behavior in our daily lives by memorizing large bodies of facts and by following explicitly represented rules. We are born with a body and the ability to feel, and we grow up as part of society. These are key elements of our intelligence and understanding. So, assuming the mind is uploaded, it still needs to contain a representation of the reality.

On the other hand, the mind needs to find meaning, and this leads us back to the fundamental issue of disembodied intelligence – how does it achieve meaning? Either someone is going to put the meaning for everything that we will understand in our representation – which is impossible because nature is infinite and things are constantly changing. Or, in the words of philosopher Merleau-Ponty, we need to go out in the world, explore it and learn about the world in our own context.

Dreyfus contradicted the formalist approach, stating that meaning is inherently context-dependent. This is known as the frame problem and is key to establishing relevance. Framing is not possible in the classical AI approach – it requires to store a model of reality within the agent. With embodied AI, the world actually become the model. Hence, we explore it and learn about it.

Dreyfus further maintained that our ability to understand the world is a non-declarative type of know-how. It is inarticulate and preconceptual, and cannot be captured by any rule-based system.

Why cognition is not only in the mind

Contrary to the Cartesian AI concept, Dreyfus encourages us to acknowledge that the brain is embodied. It gets sensory information, acts through the body, and takes an active stance. In his approach, perception is an active process, not a passive absorption of the environment. As Alva Noë puts it in Action in Perception, “perception is not a process in the brain, but a kind of skillful activity of the body as a whole.”

Enaction means that we create our own experience through our actions. In other words, we enact our perceptual experience. We do not passively receive input from the environment. We actually scan and probe the environment so we can act on it. We become actors in the environment and we shape our experience through our own actions.

Our brain is embedded in the world through the body, creating a beautiful symmetry in the circular causality: our actions upon the world become the world’s way of perceiving us.

In short, enactive cognition implies that we are in a partnership with the environment, with the world, and with the physical situation in which we find ourselves (which we mediate through our body). This partnership enables us to extend our cognition through our actions.

A masterclass of embodied and enactive AI

Dreyfus’s concept of embodied and enactive AI generated a brand new approach in cognitive science, neuroscience, and psychology – setting the stage for the implementation of the next phase in AI. His discovery allowed for significant progress in the design of truly autonomous artificial agents, as Professor Cautis from Georgetown University thoroughly explains it in the video below.

Professor Cautis’s keynote, which is the grand finale of a 4-episode series on AI, delves into the fundamental problems of classical Artificial Intelligence, introducing the salient features of embodied and enactive AI, plus some key state-of-the-art developments like the Bayesian Brain Hypothesis (BBH), the Free Energy Principle (FEP) and the Action Inference Framework (AIF).

In the philosophy-science debate, philosophers are often dismissed because they never conclude anything, whereas scientists are known for getting things done. The point that is often missed is that philosophers are there to ask questions and to think about things from a critical point of view.

Dreyfus’s questions led to a series of important discoveries and developments that professor Cautis highlighted in his keynote:

- Dreyfus’s critique of disembodied AI

- Embodied AI

- Limitations and problems of classical AI

- Fundamental problems of classical AI

– The frame problem

– The symbol grounding

– Lack of properties of embodiment and situatedness - Dennett’s robot frame problem

- Remedies & alternatives for classical AI

- Embodied and enactive AI in robotics

– What is the ecological niche

– Design of the complete agent principle

– The principle of sensory-motor coordination

– The principle of ecological balance

– The value principle - Embodied and enactive cognition

- Bayesian Brain

- Predictive processing

- Bayesian priors

- What was achieved through embodied AI

- Enactive Artificial Intelligence

- 4E cognition

- Free Energy Principle (FEE)

- Active inference

Recommended readings

- Hubert Dreyfus, What Computers Can’t Do

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception

- Alva Noe, Action in Perception (Representation and Mind Series)

- The Frame Problem

- Karl Friston, Free Energy Principle

- Jordan Peterson, Three Forms of Meaning and the Management of Complexity

No Comments